Staff Sgt. David Bellavia left Iraq a hero – the man who stormed a house in a torrent of machine gun fire in Fallujah, to save his platoon amid the bloodiest battle of the war. But when he came home, he was largely alone.

For more than a decade, he struggled with family issues, a lack of direction and place and, perhaps most of all, the loss of the brotherhood he felt with his unit: the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, or as they called themselves, the Ramrods.

Then one day in 2019 he got a call from President Donald Trump; Bellavia was to receive the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for military valor. Among his first thoughts was this: It was time to reunite the Ramrods.

This story of heroism, loss and redemption by the only living Medal of Honor Recipient from the Iraq War is recounted in his recent book, Remember the Ramrods. Bellavia, now a radio show host and podcaster in upstate New York, will appear at an Audience Meets Author event in Washington D.C. on June 13. The event is entitled “Unleash the Leader Within: The Power of Values-Based Leadership” and will feature Bellavia and Jennifer London, Ph.D, and co-author of Ever Vigilant: Leadership and Legacy by the Executive Chairman of CACI.

The free event is sponsored by the National Medal of Honor Center for Leadership, which provides leadership training based on the six values of the Medal of Honor: courage, sacrifice, integrity, commitment, patriotism and citizenship.

Bellavia recently sat down with the Center for Leadership to discuss Remember the Ramrods and the importance of values-based leadership

Q: Why did you write Remember the Ramrods?

A: Everyone wants to be like, ‘now tell your story.’ I thought, well, I wanted to tell the story of my guys. So, I wrote a memoir, but it’s about them. And I wanted to tell the things I really learned as a man. You come home from war and you’re all chewed up and you’re angry and you’re young and you’re confused.

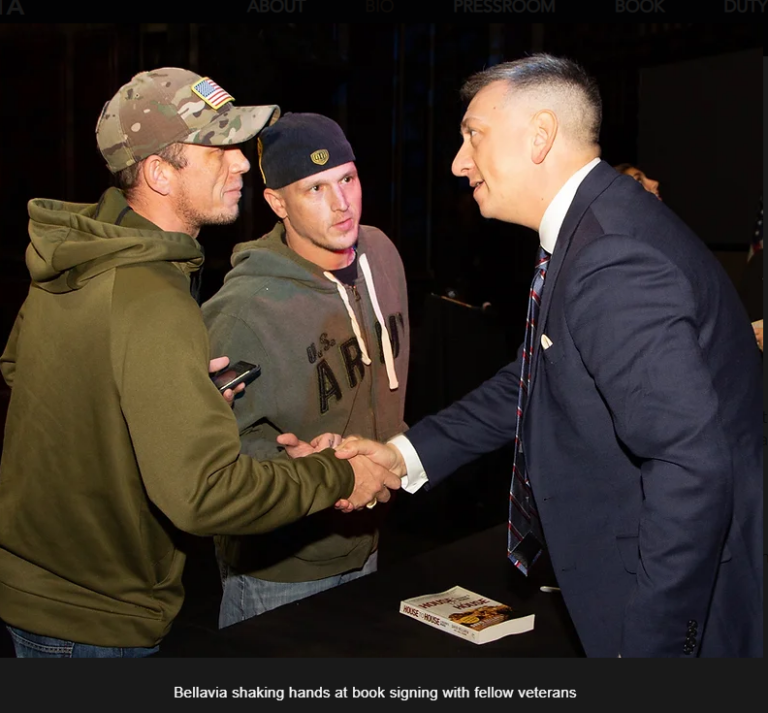

You’re traumatized, and now at work and the water cooler, and nobody understands what you’re talking about, so you just stop talking about it. And everyone went through that. So, for me, this book was needed because I wanted it to be known that we didn’t miss combat but we missed each other. And really, the takeaway is that as with the best relationships, we grew so much together and were out of each other’s lives. The Medal of Honor award brought us back together.

It’s sort of like college with a couple of firefights thrown in. You build up relationships, but life takes you miles away with your family and your priorities, and we understand that that’s a part of who we are as men. But we also understand that we have a piece of time in each other’s lives and that our job is to make everyone aware that they’re important, that they’re needed, and that no matter what happens in this world, they can come to each other and get unconditional love and that we’ll put you back together again.

"Leadership is about how I care about you. How I admire you and how I want you to be better than me because that makes our team better. Those are all values-based decisions."

- David Bellavia, Medal of Honor Recipient & Author

Q: What was harder to write about? The battlefield experiences or the personal toll it took on you and the relationships with these men? These are not necessarily things that men often talk about.

A: But that’s the problem. When you’re in your twenties, you can’t tell another guy you love him – that’s weird. Anything personal for an infantryman is difficult. And then you hit like middle age, and you’re like, l want to take advantage of this moment right now to say that you’re special, that I admire you, I love you, and I appreciate you.

Q: Some of those things are gut wrenching. Like when you came home from the deployment, you land in Germany and your family isn’t there, and you’re by yourself.

A: It wasn’t just me that was going through it. The number one casualty of the War on Terror is divorce. You build up to be an alpha and handle anything, and then you get your heart broken or your business goes bust or, you know, something happens that you’re not prepared for. And now we’re like, wait a minute, what do we do? It turns out that it’s the same thing you do when you’re shot at, you adapt, overcome, come up with a new plan, try something.

I realized how much of the fight I lost in the civilian world. But then I got my fight back, and I got my purpose back. And I think that’s what we really long for as veterans, that you have a purpose.

Q: How important have values been in your experiences? Do they help provide the purpose?

A: If you ask an infantryman what is the one thing I can master as a soldier, it’s to be the most competent infantryman that you’ve ever met.

And when you boil competency down, the building blocks start with character. That’s what it’s all about because you can be the best at what you are; you can have a brilliant skill set, but no one will want to approach you if you’re pompous, you’re arrogant, you’re selfish, or if you’re not part of the team.

Teams are built by men and women leaders who always put the good of everyone above themselves. This is intrinsic in not only building teams, but also in having success. How do you guarantee success? Knowing that it’s not just my brain, it’s her brain and his brain. We’re all committed to this. And we don’t care who gets the credit, it’s going to get done.

Leadership is about how I care about you. How I admire you and how I want you to be better than me because that makes our team better. Those are all values-based decisions.

Q: How do you reconcile the values we’re talking about with extreme violence?

A: It’s just tough. As a Christian, I’ve got two brothers who went to seminary, and we were a very religious family.

It’s funny, I got the Medal of Honor and they sent me to Gay Pride Week in New York. It was the first event I did with the Army, and I had no idea how would I be perceived, what would happen. Well, I got stopped in the street and thanked for my service. What I’ve learned is that whether you’re West Coast, East Coast, at rodeos, fairs, you name it, America is still America.

I go to Broadway and there’s this actor, and the guy has so much swagger and so much confidence, and he walks out onto the stage after a Broadway show and he asked me, ‘You know, Staff Sergeant, do you know why you fight so hard when you’re at war?’ And I’m like, ‘So you can tap dance?’ And this guy just shut me down. He says, ‘No, we dance on stage so you have something to fight for.’

And I was so mad because this Broadway guy floored me and absolutely changed the way I look at the world. That’s why we fight for America. We don’t hate our enemy. We love our country. We don’t hate what we fight. We love what we’re protecting.

Q: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to young professionals as they take on leadership roles?

A: Screw up and don’t depend on other people for validation. You’re going to make mistakes. You’re never going to learn unless you make those mistakes. A person who is not making errors is a person I have no use for because all they’re doing is regurgitating what we’re doing now at a certain level.

We’ve got to accept the idea that sometimes we win, sometimes we lose but it’s going to be absolutely fine, and we’re going to maintain our bearings throughout. You need to build those fundamentals of dealing with rejection, learning how to fail, and understanding that your opinion of me does not impact me as much as my opinion of me.

Q: One last question for you. Are you optimistic about America?

A: That’s the definition of being an American. We have to be optimistic. It’s the basis of the American dream. Why not me?

To RVSP for the Audience Meets Author event, CLICK HERE

You can lead an impactful life by learning more about the six core values of the Medal of Honor – Courage, Integrity, Commitment, Sacrifice, Citizenship, and Patriotism. To get started, read more on our Values-Based Leadership Education Program.

To purchase David’s Books – click the image: